- جدید

- ناموجود

توجه : درج کد پستی و شماره تلفن همراه و ثابت جهت ارسال مرسوله الزامیست .

توجه:حداقل ارزش بسته سفارش شده بدون هزینه پستی می بایست 180000 ریال باشد .

| This is an old revision of this page, as edited by BattyBot (talk | contribs) at 04:34, 18 April 2014 (→Later years and death: fixed CS1 errors: dates to meet MOS:DATEFORMAT (also General fixes) using AWB (10069)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision. |

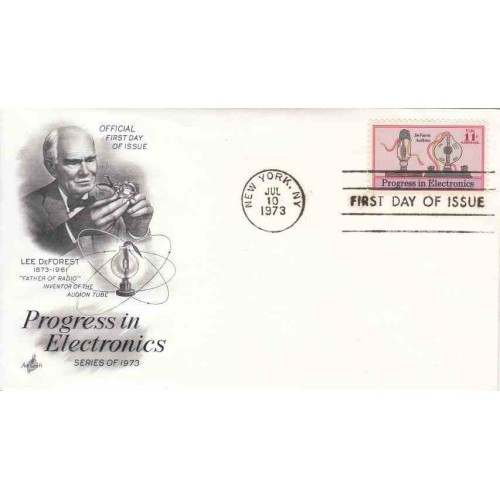

| Lee de Forest | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | August 26, 1873 Council Bluffs, Iowa |

| Died | June 30, 1961 (aged 87) Hollywood, California |

| Occupation | Inventor |

| Known for | inventions |

| Spouse(s) | Lucille Sheardown (m.1906; divorced) Nora Stanton Blatch Barney (m.1907-1911; divorced) Mary Mayo (m.1912-1923; divorced) Marie Mosquini (m.1930-1961; his death) |

| Parent(s) | Henry Swift DeForest Anna Robbins |

| Relatives | Calvert DeForest (grandnephew) |

Lee de Forest (August 26, 1873 – June 30, 1961) was an American inventor with over 180 patents to his credit. He named himself the "Father of Radio," with this famous quote, "I discovered an Invisible Empire of the Air, intangible, yet solid as granite,".[1]

In 1906 De Forest invented the Audion, the first triode vacuum tube and the first electrical device which could amplify a weak electrical signal and make it stronger. The Audion, and vacuum tubes developed from it, founded the field of electronics and dominated it for 40 years, making radio broadcasting, television, and long-distance telephone service possible, among many other applications. For this reason De Forest has been called one of the fathers of the "electronic age". He is also credited with one of the principal inventions that brought sound to motion pictures.

He was involved in several patent lawsuits, and spent a substantial part of his income from his inventions on legal bills. He had four marriages and 25 companies. He was indicted for mail fraud, but later was acquitted.

De Forest was a charter member of the Institute of Radio Engineers. DeVry University was originally named DeForest Training School by its founder Dr. Herman A. DeVry, who was a friend and colleague of De Forest.

Lee De Forest was born in 1873 in Council Bluffs, Iowa, the son of Anna Margaret (née Robbins) and Henry Swift De Forest.[2][3] He was a direct descendant of Jessé de Forest who was the leader of a group of Walloon Huguenots who fled Europe due to religious persecutions.

His father was a Congregational Church minister who hoped that his son would also become a minister. Henry Swift DeForest accepted the position of President of Talladega College, a traditionally African American school, in Talladega, Alabama, where Lee spent most of his youth. Many citizens of the white community resented his father's efforts to educate African Americans. Growing up, De Forest had several friends among the black children of the town.

De Forest attended Mount Hermon School, and in 1893 enrolled at the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University in Connecticut. As an inquisitive young inventor, he tapped into the electrical system at Yale one evening and completely blacked out the entire campus, causing his suspension. He was eventually allowed to complete his studies, receiving his bachelor's degree in 1896. He paid part of his tuition with the income from his mechanical and gaming inventions. De Forest earned his Ph.D. degree in 1899 with a dissertation on radio waves, supervised by theoretical physicist Willard Gibbs. For the next two years, he was on faculty at Armour Institute of Technology and Lewis Institute (merging in 1940 to become Illinois Institute of Technology physics department) and conducted his first long-distance broadcasts from the university.

In 1901 DeForest fell into competition with Guglielmo Marconi at the New York’s International Yacht Races, each working for rival news services, and using their own inventions. Marconi used his patented wireless telegraphy and DeForest his transmitter and receiver, which was not yet patented. They sat on separate boats, and transmitted the highlights of the race live. Unfortunately they jammed each other’s signals, and neither of the two men were able to transmit any news of the race. DeForest, in a fit of rage, threw his transmitter overboard. Jammed frequencies were a common problem in the very early years of radio.[4]

De Forest was interested in wireless telegraphy and invented the Audion in 1906. He then developed an improved wireless telegraph receiver.

On 25 October 1906,[5] de Forest filed a patent for diode vacuum tube detector, a two-electrode device for detecting electromagnetic waves, a variant of the Fleming valve invented two years earlier. One year later, he filed a patent for a three-electrode device that was a much more sensitive detector of electromagnetic waves. It was granted US Patent 879,532 in February 1908. The device was also called the de Forest valve, and since 1919 has been known as the triode. De Forest's innovation was the insertion of a third electrode, the grid, between the cathode (filament) and the anode (plate) of the previously invented diode. The resulting triode or three-electrode vacuum tube could be used as an amplifier of electrical signals, notably for radio reception. The Audion was the fastest electronic switching element of the time, and was later used in early digital electronics (such as computers). The triode was vital in the development of transcontinental telephone communications, radio, and radar until the 1948 invention of the transistor.

De Forest had, in fact, stumbled onto this invention via tinkering and did not completely understand how it worked. De Forest had initially claimed that the operation was based on ions created within the gas in the tube when, in fact, it was shown by others to operate with a vacuum in the tube. The device was subsequently carefully investigated by H. D. Arnold and his team at Western Electric (AT&T) and Irving Langmuir at the General Electric Corp. Both of them correctly explained the theory of operation of the device and provided significant improvements in its construction.

In 1904, a De Forest transmitter and receiver were set up aboard the steamboat Haimun operated on behalf of The Times, the first of its kind.[6] On July 18, 1907, De Forest broadcast the first ship-to-shore message from the steam yacht Thelma. The communication provided quick, accurate race results of the Annual Inter-Lakes Yachting Association (I-LYA) Regatta. The message was received by his assistant, Frank E. Butler of Monroeville, Ohio, in the Pavilion at Fox's Dock located on South Bass Island on Lake Erie. DeForest disliked the term "wireless" and chose a new moniker, "radio." De Forest is credited with the birth of public radio broadcasting when on January 12, 1910, he conducted experimental broadcast of part of the live performance of Tosca and, the next day, a performance with the participation of the Italian tenor Enrico Caruso from the stage of Metropolitan Opera House in New York City.[7] [8]

De Forest came to San Francisco in 1910, and worked for the Federal Telegraph Company, which began developing the first global radio communications system in 1912. California Historical Landmark No. 836 is a bronze plaque at the eastern corner of Channing St. and Emerson Ave. in Palo Alto, California, which memorializes the Electronics Research Laboratory at that location and De Forest for the invention of the three-element radio vacuum tube.

The United States Attorney General sued De Forest for fraud (in 1913) on behalf of his shareholders, stating that his claim of regeneration was an "absurd" promise (he was later acquitted). Nearly bankrupt with legal bills, De Forest sold his triode vacuum-tube patent to AT&T and the Bell System in July 1913 for the price of $50,000. This gave AT&T rights to use and build the Audion except for wireless telegraphy. De Forest would sell the rights for wireless telegraphy for $90,000 on August 1914.[to whom?] He would later relinquish all rights to AT&T retaining to himself in March 1917 for $250,000.[9]

De Forest tried again to start another business venture. This time making high power tubes used as an oscillator for wireless telegraphy and amateur radio transmissions. These tubes were called oscillions. De Forest wanted to keep a tight hold on his tube business by demanding retailers that their customers must return their worn out tube before they can get another. This style of business encouraged others to make and sell counterfeit or bootleg vacuum tubes which did not require a return policy. One of the boldest was Audio Tron Sales Company founded by Elmer T. Cunningham of San Francisco. He came up with the Audio Tron which was lower in price yet of high quality. Amateur radio experimenters were buying Audio Trons and it cut into De Forest's business. He would later sue Audio Tron Sales but settled out of court.[10]

De Forest filed another patent in 1916 that became the cause of a contentious lawsuit with the prolific inventor Edwin Howard Armstrong, whose patent for the regenerative circuit had been issued in 1914. The lawsuit lasted twelve years, winding its way through the appeals process and ending up before the Supreme Court in 1926. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of De Forest, although the view of many historians is that the judgment was incorrect.[11] Over time radio history has credited Lee De Forest as the inventor of the three element or triode vacuum tube and Edwin Armstrong is the inventor of radio (regeneration and superheterodyne). Armstrong in a sense showed De Forest how the Audion works and what it can be used for.[12]

In 1916, De Forest, from experimental radio station 2XG in New York City, broadcast the first radio advertisements (for his own products) and the first Presidential election report by radio in November 1916 for Charles Evans Hughes and Woodrow Wilson. A few months later, DeForest moved his tube transmitter to Highbridge, Bronx.[13] Like Charles Herrold in San Jose, California,—who had been broadcasting since 1909 with call letters "FN," "SJN," and then "6XF"—De Forest had a license from the Department of Commerce for an experimental radio station, but, like Herrold, had to cease all broadcasting when the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917. From April 1920 to November 1921, DeForest broadcast from station 6XC at the California Theater at Market and Fourth Streets in San Francisco. In late 1921, 6XC moved its transmitter to Ocean View Drive in the Rockridge section of Oakland, California, and became KZY.[14][15]

Just like Pittsburgh’s KDKA, four years later in November 1920, DeForest used the Hughes/Wilson presidential election returns for his broadcast. The New York American installed a private wire and bulletins were sent out every hour. About 2000 listeners heard The Star-Spangled Banner and other anthems, songs, and hymns. DeForest went on to sponsor radio broadcasts of music, featuring opera star Enrico Caruso and many other events, but he received little financial backing.

In April 1923, the De Forest Radio Telephone & Telegraph Company, which manufactured De Forest's Audions for commercial use, was sold to a coalition of automobile makers who expanded the company's factory to cope with rising demand for radios. The sale also bought the services of De Forest, who was focusing his attention on newer innovations.[16]

In 1919, De Forest filed the first patent on his sound-on-film process, which improved on the work of Finnish inventor Eric Tigerstedt and the German partnership Tri-Ergon, and called it the De Forest Phonofilm process. Phonofilm recorded sound directly onto film as parallel lines of variable shades of gray, and later became known as a "variable density" system as opposed to "variable area" systems such as RCA Photophone. These lines photographically recorded electrical waveforms from a microphone, which were translated back into sound waves when the movie was projected.

From October 1921 to September 1922, DeForest lived in Berlin, meeting with the Tri-Ergon developers and investigating other European sound film systems. He announced to the press in April 1922 that he would soon have a workable sound-on-film system.[17]

On 12 March 1923, DeForest presented a demonstration of Phonofilm to the press.[18] On 12 April 1923, DeForest gave a private demonstration of the process to electrical engineers at the Engineering Society Building's Auditorium at 33 West 39th Street in New York City.[19]

This system, which synchronized sound directly onto film, was used to record stage performances (such as in vaudeville), speeches, and musical acts. In November 1922, De Forest established his De Forest Phonofilm Company at 314 East 48th Street in New York City, but none of the Hollywood movie studios expressed any interest in his invention.

De Forest premiered 18 short films made in Phonofilm on 15 April 1923 at the Rivoli Theater in New York City. He was forced to show his films in independent theaters such as the Rivoli, since Hollywood movie studios controlled all major theater chains. De Forest chose to film primarily short vaudeville acts, not features, limiting the appeal of his process to Hollywood studios. Max Fleischer and Dave Fleischer used the Phonofilm process for their Song Car-Tune series of cartoons—featuring the "Follow the Bouncing Ball" gimmick—starting in May 1924.

De Forest also worked with Freeman Harrison Owens and Theodore Case, using Owens's and Case's work to perfect the Phonofilm system. However, DeForest had a falling out with both men. Due to DeForest's continuing misuse of Theodore Case's inventions and failure to publicly acknowledge Case's contributions, the Case Research Lab proceeded to build its own camera. That camera was used by Case and his colleague Earl Sponable to record President Coolidge on 11 August 1924, which was one of the films shown by DeForest and claimed by him to be the product of "his" inventions. Seeing that DeForest was more concerned with his own fame and recognition than he was with actually creating a workable system of sound film, and because of DeForest's continuing attempts to downplay the contributions of the Case Research Lab in the creation of Phonofilm, Case severed his ties with DeForest in the fall of 1925.

Case then negotiated an agreement for his patents with studio head William Fox, owner of Fox Film Corporation, who marketed the system as the Fox Movietone process. Shortly before the Phonofilm Company filed for bankruptcy in September 1926, Hollywood introduced a new method for sound film, the sound-on-disc process developed by Warner Brothers as Vitaphone, with the John Barrymore film Don Juan, released 6 August 1926.

In 1927 and 1928, Hollywood began to use sound-on-film systems, including Fox Movietone and RCA Photophone. Meanwhile, a theater chain owner, Isadore Schlesinger, acquired the UK rights to Phonofilm and released short films of British music hall performers from September 1926 to May 1929. Almost 200 short films were made in the Phonofilm process, and many are preserved in the collections of the Library of Congress and the British Film Institute.[20]

De Forest sold one of his radio manufacturing firms to RCA in 1931. In 1934, the courts sided with De Forest against Edwin Armstrong.

In 1940 he sent an open letter to the National Association of Broadcasters in which he demanded to know, "What have you done with my child, the radio broadcast? You have debased this child, dressed him in rags of ragtime, tatters of jive and boogie-woogie."

Also in 1940, De Forest and early TV engineer Ulises Armand Sanabria presented the concept of a primitive unmanned combat air vehicle using a television camera and a jam resistant radio control in a Popular Mechanics issue.[21]

De Forest authored an autobiography Father of Radio in 1950.

De Forest was the guest celebrity on the May 22, 1957, episode of the television show This Is Your Life, where he was introduced as "the father of radio and the grandfather of television." Highlights of this episode, as well as a film clip of his 1940 NAB letter, can be found in the 1992 Ken Burns PBS documentary film based on Tom Lewis' book Empire of the Air: The Men Who Made Radio.

De Forest's initially rejected, but later adopted, movie soundtrack method brought De Forest an Academy Award in 1959/1960 for "his pioneering inventions which brought sound to the motion picture" and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

On his religious views, he was an agnostic.[22][23]

He suffered a severe heart attack in 1958, and remained mostly bedridden.[24]

He died in Hollywood on June 30, 1961, aged 87, and was interred in San Fernando Mission Cemetery in Los Angeles, California.[25] De Forest died relatively poor, with just $1,250 in his bank account.[26]

De Forest's archives were donated through his widow to the Perham Electronic Foundation, and housed in a museum at Foothill College in Los Altos. In 1991 the college broke its contract and closed the museum. The foundation later won a lawsuit and was awarded $775,000. The archives are stored in San Jose, waiting for space, perhaps in the San Jose Historical Park.[27]

De Forest received the IRE Medal of Honor in 1922, as "recognition for his invention of the three-electrode amplifier and his other contributions to radio."[28] He was awarded the Franklin Institute's Elliott Cresson Medal in 1923. In 1946, he received the Edison Medal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers 'For the profound technical and social consequences of the grid-controlled vacuum tube which he had introduced'. An important annual medal awarded to engineers by the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers is named the Lee De Forest Medal.

De Forest was a conservative Republican and fervent anti-communist and anti-fascist. In 1932, he had voted for Franklin Roosevelt, in the midst of the Great Depression, but later came to resent him, calling Roosevelt America's "first Fascist president." In 1949, he "sent letters to all members of Congress urging them to vote against socialized medicine, federally subsidized housing, and an excess profits tax." In 1952, he wrote newly elected Vice President Richard Nixon, urging him to "prosecute with renewed vigor your valiant fight to put out Communism from every branch of our government." In December 1953, he cancelled his subscription to The Nation, accusing it of being "lousy with Treason, crawling with Communism."[29]

De Forest was given to expansive predictions, many of which were not borne out, but he also made many correct predictions, including microwave communication and cooking.

Lee de Forest had four wives:

Patent images in TIFF format