- جدید

- ناموجود

توجه : درج کد پستی و شماره تلفن همراه و ثابت جهت ارسال مرسوله الزامیست .

توجه:حداقل ارزش بسته سفارش شده بدون هزینه پستی می بایست 100000 ریال باشد .

توجه : جهت برخورداری از مزایای در نظر گرفته شده برای مشتریان لطفا ثبت نام نمائید.

| Giotto di Bondone | |

|---|---|

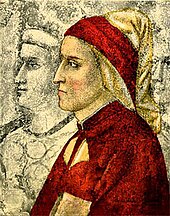

Possible image of Giotto from the Peruzzi Chapel (digitally restored)

|

|

| Born | Giotto di Bondone 1266/7 near Florence, Republic of Florence, in present-day Italian Republic |

| Died | January 8, 1337 (aged about 70) Florence, Republic of Florence, in present-day Italian Republic |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting, Fresco, Architecture |

| Notable work | Scrovegni Chapel frescoes, Campanile |

| Movement | Late Gothic Proto-Renaissance |

Giotto di Bondone (1266/7 – January 8, 1337), known as Giotto (Italian: [ˈdʒɔtto]), was an Italian painter and architect from Florence in the late Middle Ages. He is generally considered the first in a line of great artists who contributed to the Renaissance.

Giotto's contemporary, the banker and chronicler Giovanni Villani, wrote that Giotto was "the most sovereign master of painting in his time, who drew all his figures and their postures according to nature. And he was given a salary by the Comune of Florence in virtue of his talent and excellence."[1]

The late-16th century biographer Giorgio Vasari describes Giotto as making a decisive break with the prevalent Byzantine style and as initiating "the great art of painting as we know it today, introducing the technique of drawing accurately from life, which had been neglected for more than two hundred years."[2]

Giotto's masterwork is the decoration of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, also known as the Arena Chapel, completed around 1305. This fresco cycle depicts the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ. It is regarded as one of the supreme masterpieces of the Early Renaissance.[3] That Giotto painted the Arena Chapel and that he was chosen by the Comune of Florence in 1334 to design the new campanile (bell tower) of the Florence Cathedral are among the few certainties of his biography. Almost every other aspect of it is subject to controversy: his birthdate, his birthplace, his appearance, his apprenticeship, the order in which he created his works, whether or not he painted the famous frescoes at Assisi, and his burial place.

Tradition holds that Giotto was born in a farmhouse, perhaps at Colle di Romagnano or Romignano;[4] since 1850 a tower house in nearby Colle Vespignano, a hamlet 35 kilometres north of Florence, has borne a plaque claiming the honour of his birthplace, an assertion commercially publicized. Very recent research, however, has suggested that he was actually born in Florence, the son of a blacksmith.[5] His father's name was Bondone, described in surviving public records as "a person of good standing". Most authors accept that Giotto was his real name, but it may have been an abbreviation of Ambrogio (Ambrogiotto) or Angelo (Angelotto).[6]

The year of his birth is calculated from the fact that Antonio Pucci, the town crier of Florence, wrote a poem in Giotto's honour in which it is stated that he was 70 at the time of his death. However, the word "seventy" fits into the rhyme of the poem better than would have a longer and more complex age, so it is possible that Pucci used artistic license.[6]

In his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Giorgio Vasari relates that Giotto was a shepherd boy, a merry and intelligent child who was loved by all who knew him. The great Florentine painter Cimabue discovered Giotto drawing pictures of his sheep on a rock. They were so lifelike that Cimabue approached Bondone and asked if he could take the boy as an apprentice.[2] Cimabue was one of the two most highly renowned painters of Tuscany, the other being Duccio, who worked mainly in Siena.

Vasari recounts a number of such stories about Giotto's skill. He writes that when Cimabue was absent from the workshop, his young apprentice painted such a lifelike fly on the face of the painting that Cimabue was working on, that he tried several times to brush it off.

Vasari also relates that when the Pope sent a messenger to Giotto, asking him to send a drawing to demonstrate his skill, Giotto drew, in red paint, a circle so perfect that it seemed as though it was drawn using a pair of compasses and instructed the messenger to give that to the Pope. According to Vasari, "the messenger departed ill pleased, not doubting that he had been made a fool of. However, sending the other drawings to the Pope with the names of those who had made them, he sent also Giotto's, relating how he had made the circle without moving his arm and without compasses, which when the Pope and many of his courtiers understood, they saw that Giotto must surpass greatly all the other painters of his time."[2] The incident led to a proverb, "You are rounder than the O of Giotto" that was apparently still used in Vasari's time to describe a dim- or slow-witted person; "round" meaning both a perfect circle, as well as slowness and heaviness of mind.[2]

Many scholars today are uncertain about Giotto's training, and consider that Vasari's story that he was Cimabue's pupil is legendary, citing early sources which suggest that Giotto was not Cimabue's pupil.[7] Giotto's art shares many qualities with Roman paintings of the later 13th century. Cimabue may have been working in Rome in this period, and there was an active local school of fresco painters, of whom the most famous was Pietro Cavallini. The famous Florentine sculptor and architect, Arnolfo di Cambio, was then also working in Rome.[2] Giotto is generally regarded as the one who reintroduced realistic expression into Western art; furthermore, his art displays sometimes unprecedented iconography and self-reflexive imagery.[8]

From Rome, Cimabue went to Assisi to paint several large frescoes at the newly built Basilica of St Francis of Assisi, and it is possible, but not certain, that Giotto went with him. The attribution of the fresco cycle of the Life of St. Francis in the Upper Church has been one of the most hotly disputed in art history. The documents of the Franciscan Friars that relate to artistic commissions during this period were destroyed by Napoleon's troops, who stabled horses in the Upper Church of the Basilica, and scholars have been divided over whether or not Giotto was responsible for the Francis Cycle. In the absence of documentary evidence to the contrary, it has been convenient to ascribe every fresco in the Upper Church that was not obviously by Cimabue to Giotto, whose prestige has overshadowed that of almost every contemporary.

An early biographical source, Riccobaldo Ferrarese, mentions that Giotto painted at Assisi, without specifying the St Francis Cycle: "What kind of art [Giotto] made is testified to by works done by him in the Franciscan churches at Assisi, Rimini, Padua..."[9] Since the idea was put forward by the German art historian, Friedrich Rintelen in 1912,[10] many scholars have expressed doubt that Giotto was in fact the author of the Upper Church frescoes.

Without documentation, arguments on the attribution have relied upon connoisseurship, a notoriously unreliable "science";[11] however, technical examinations and comparisons of the workshop painting processes at Assisi and Padua in 2002 have provided strong evidence that Giotto did not paint the St. Francis Cycle.[12] There are many differences between the Francis Cycle and the Arena Chapel frescoes that are difficult to account for by the stylistic development of an individual artist. It is now generally accepted that four different hands are identifiable and that these artists came from Rome. If this is the case, then Giotto's frescoes at Padua owe much to the naturalism of these painters.[6]

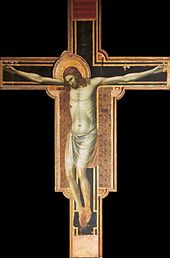

The authorship of a large number of panel paintings ascribed to Giotto by Vasari, among others, is as broadly disputed as the Assisi frescoes.[13] According to Vasari, Giotto's earliest works were for the Dominicans at Santa Maria Novella. These include a fresco of the Annunciation and the enormous suspended Crucifix, which is about 5 metres high.[2] It has been dated around 1290 and is therefore contemporary with the Assisi frescoes.[14] Other early works are the San Giorgio alla Costa Madonna and Child now in the Diocesan Museum of Santo Stefano al Ponte, Florence, and the signed panel of the Stigmata of St. Francis, once in San Francesco at Pisa, today in the Louvre.

In 1287, at the age of about 20, Giotto married Ricevuta di Lapo del Pela, known as "Ciuta". The couple had numerous children, (perhaps as many as eight) one of whom, Francesco, became a painter.[6] Giotto worked in Rome in 1297–1300, but few traces of his presence there remain today. The Basilica of St. John Lateran houses a small portion of a fresco cycle, painted for the Jubilee of 1300 called by Boniface VIII. In this period Giotto also painted the Badia Polyptych, now in the Uffizi, Florence.[2]

Giotto's fame as a painter spread. He was called to work in Padua, and also in Rimini, where today there remains only a Crucifix painted before 1309 and conserved in the Church of St. Francis.[2] This work influenced the rise of the Riminese school of Giovanni and Pietro da Rimini. According to documents of 1301 and 1304, Giotto by this time possessed large estates in Florence, and it is probable that he was already leading a large workshop and receiving commissions from throughout Italy.[6]

Around 1305 Giotto executed his most influential work, the painted decoration of the interior of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. Enrico degli Scrovegni commissioned the chapel to serve as a family worship and burial space, even though his parish church was nearby; its construction caused some consternation among the clerics at the Eremitani church next door.[15]

It has also been speculated that Enrico commissioned the chapel as a penitence for his sin of usury (i.e. charging interest for lending money), which at the time was considered unjust. In fact, Dante himself accused Enrico's father of it and condemned him in his Divine Comedy.[16] The presence of Enrico near the center of The Final Judgement, handing the Arena Chapel to the Three Marys, on the virtuous side of the judgement and not with the other usurers (shown hanging by the strings of their money bags on the opposite side) may also be seen as proof of his repentance. This chapel is externally a very plain building of pink brick which was constructed next to an older palace that Scrovegni was restoring for himself. The palace, now gone, and the chapel were on the site of a Roman arena, for which reason it is commonly known as the Arena Chapel.[6]

The theme is Salvation, and there is an emphasis on the Virgin Mary, as the chapel is dedicated to the Annunciation and to the Virgin of Charity. As is common in the decoration of the medieval period in Italy, the west wall is dominated by the Last Judgement. On either side of the chancel are complementary paintings of the Angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary, depicting the Annunciation. This scene is incorporated into the cycles of The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary and The Life of Christ. The source for The Life of the Virgin is the Golden Legend of Jacopo da Voragine while The Life of Christ draws upon the Meditations on the Life of Christ by the Pseudo-Bonaventura. The frescoes are more than mere illustrations of familiar texts, however, and scholars have found numerous sources for Giotto's interpretations of sacred stories.[17]

The cycle is divided into 37 scenes, arranged around the lateral walls in three tiers, starting in the upper register with the story of Joachim and Anna, the parents of the Virgin and continuing with the story of Mary. The life of Jesus occupies two registers. The Last Judgment fills the entire pictorial space of the counter-façade.

The top right hand tier deals with the lives of Mary's parents, the left with her early life, and the middle tier with the early life and miracles of Christ.

The bottom tier on both sides is concerned with the Passions of Christ. He is depicted mainly in profile, as is customary, historically, when depicting persons of importance. His eyes point continuously to the right, perhaps to guide the viewer onwards in the episodes. The kiss of Judas near the end of the sequence signals the close of this left-to-right procession.

Below the narrative scenes in color, Giotto also painted the allegories of seven Virtues and their counterparts in monochrome gray. The monochrome frescoes appear as marble statues. Furthermore, the allegories of Justice and Injustice in the middle of the sequence oppose two specific types of government: peace leading to a festival of Love and tyranny resulting in wartime rape.[18]

Much of the blue in the fresco has been worn away by time. This is because Enrico degli Scrovegni ordered that, because of the expense of the pigment ultramarine blue used, it should be painted on top of the already dry fresco (secco fresco) to preserve its brilliance. For this reason it has disintegrated faster than the other colors which have been fastened within the plaster of the fresco. An example of this decay can clearly be seen on the robe of Christ as he sits on the donkey.

Between the scenes are quatrefoil paintings of Old Testament scenes, like Jonah and the Whale that allegorically correspond and perhaps foretell the life of Christ.

While Cimabue painted in a manner that is clearly Medieval, having aspects of both the Byzantine and the Gothic, Giotto's style draws on the solid and classicizing sculpture of Arnolfo di Cambio. Unlike those by Cimabue and Duccio, Giotto's figures are not stylized or elongated and do not follow the Byzantine models of his contemporaries. They are solidly three-dimensional, have faces and gestures that are based on close observation, and are clothed not in swirling formalized drapery, but in garments that hang naturally and have form and weight. He also took bold steps in foreshortening and with having characters face inwards, with their backs towards the observer creating the illusion of space.

The figures occupy compressed settings with naturalistic elements, often using forced perspective devices so that they resemble stage sets. This similarity is increased by Giotto's careful arrangement of the figures in such a way that the viewer appears to have a particular place and even an involvement in many of the scenes. This can be seen most markedly in the arrangement of the figures in the Mocking of Christ and Lamentation where the viewer is bidden by the composition that Giotto has created to become mocker in one and mourner in the other.

Famous narratives in the series include the Adoration of the Magi, in which a comet-like Star of Bethlehem streaks across the sky. Giotto is thought to have been inspired by the 1301 appearance of Halley's comet, which led to the name Giotto being given to a 1986 space probe to the comet.

Giotto's depiction of the human face and emotion sets his work apart from that of his contemporaries. When the disgraced Joachim returns sadly to the hillside, the two young shepherds look sideways at each other. The soldier who drags a baby from its screaming mother in the Massacre of the Innocents does so with his head hunched into his shoulders and a look of shame on his face. The people on the road to Egypt gossip about Mary and Joseph as they go. Of Giotto's realism, the 19th-century English critic John Ruskin said "He painted the Madonna and St. Joseph and the Christ, yes, by all means ... but essentially Mamma, Papa and Baby."[6]

Besides his pivotal contribution to the development of a new realistic visual language, Giotto might have been also responsible for the reintroduction of true fresco technique to Western art. This technological development allowed the creation of more durable murals with unprecedented colors and brilliance.[19]

Among those frescoes in Padua which have been lost are those in the Basilica of. St. Anthony[20] and the Palazzo della Ragione,[21] which are however from a later sojourn in Padua.

Numerous painters from northern Italy were influenced by Giotto's work in Padua including Guariento, Giusto de' Menabuoi, Jacopo Avanzi, and Altichiero.

From 1306 to 1311 Giotto was in Assisi, where he painted frescoes in the transept area of the Lower Church, including The Life of Christ, Franciscan Allegories and the Maddalena Chapel, drawing on stories from the Golden Legend and including the portrait of bishop Teobaldo Pontano who commissioned the work. Several assistants are mentioned, including one Palerino di Guido. However, the style demonstrates developments from Giotto's work at Padua.[6]

In 1311 Giotto returned to Florence. A document from 1313 about his furniture there shows that he had spent a period in Rome some time before. It is now thought that he produced the design for the famous Navicella mosaic for the courtyard of the Old St. Peter's Basilica in 1310, commissioned by Cardinal Giacomo or Jacopo Stefaneschi and now lost to the Renaissance church, except for some fragments and a Baroque reconstruction. According to the cardinal's necrology he also at least designed the Stefaneschi Triptych, a double-sided altarpiece for St. Peter's, now in the Vatican Pinacoteca. But the style seems unlikely for either Giotto or his normal Florentine assistants, so he may have had his design executed by an ad hoc workshop of Romans.[22]