- جدید

- ناموجود

توجه : درج کد پستی و شماره تلفن همراه و ثابت جهت ارسال مرسوله الزامیست .

توجه:حداقل ارزش بسته سفارش شده بدون هزینه پستی می بایست 100000 ریال باشد .

توجه : جهت برخورداری از مزایای در نظر گرفته شده برای مشتریان لطفا ثبت نام نمائید.

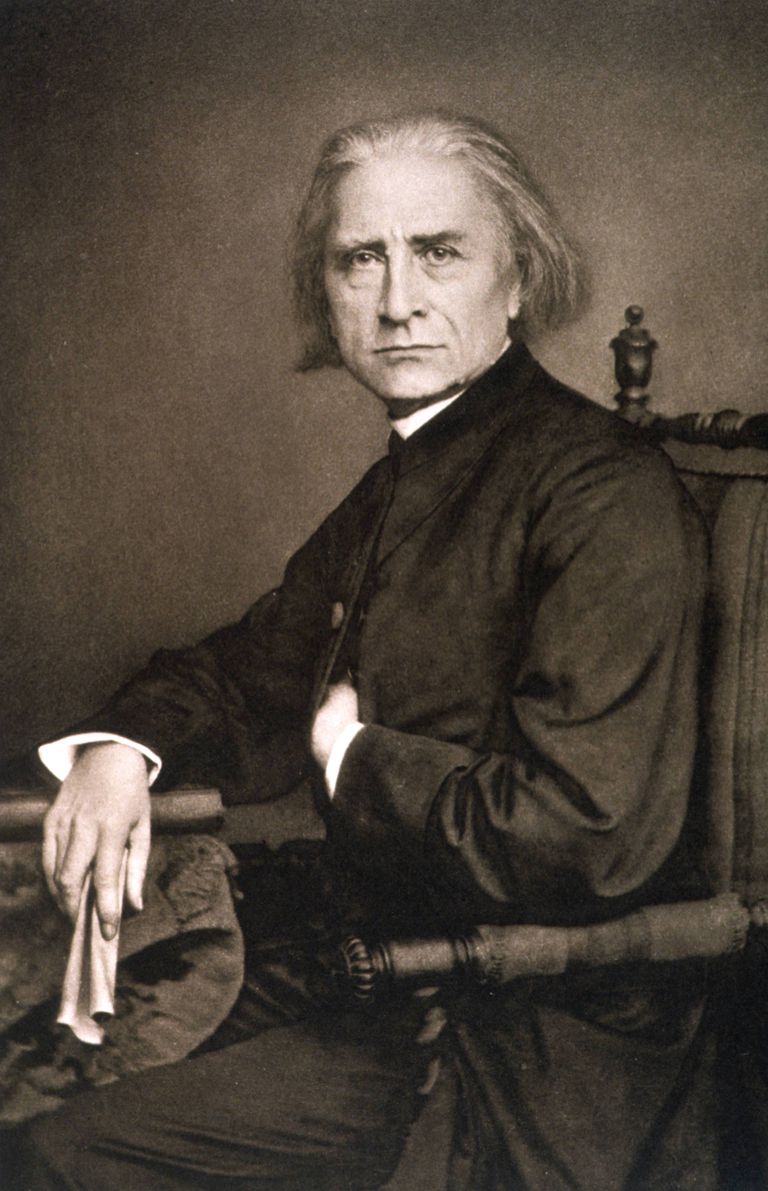

Franz Liszt (German pronunciation: [ˈfʁants ˈlɪst]; Hungarian: Liszt Ferencz, in modern usage Liszt Ferenc, pronounced [ˈlist ˈfɛrɛnt͡s];[n 1] October 22, 1811 – July 31, 1886) was a prolific 19th-century Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor, music teacher, arranger, philanthropist, author, nationalist and a Franciscan tertiary.

Liszt gained renown in Europe during the early nineteenth century for his prodigious virtuosic skill as a pianist. He was said by his contemporaries to have been the most technically advanced pianist of his age, and in the 1840s he was considered to be the greatest pianist in history. However, Liszt himself stated that Charles-Valentin Alkan had superior technique to his own. Liszt was also a well-known and influential composer, piano teacher and conductor. He was a benefactor to other composers, including Frédéric Chopin, Richard Wagner, Hector Berlioz, Camille Saint-Saëns, Edvard Grieg, Ole Bull and Alexander Borodin.[1]

As a composer, Liszt was one of the most prominent representatives of the New German School (Neudeutsche Schule). He left behind an extensive and diverse body of work in which he influenced his forward-looking contemporaries and anticipated some 20th-century ideas and trends. Some of his most notable contributions were the invention of the symphonic poem, developing the concept of thematic transformation as part of his experiments in musical form, and making radical departures in harmony.[2] He also played an important role in popularizing a wide array of music by transcribing it for piano.

Franz Liszt was born to Anna Liszt (née Maria Anna Lager)[3] and Adam Liszt on October 22, 1811, in the village of Doborján (German: Raiding) in Sopron County, in the Kingdom of Hungary.[n 2] Liszt's father played the piano, violin, cello and guitar. He had been in the service of Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy and knew Haydn, Hummel and Beethoven personally. At age six, Franz began listening attentively to his father's piano playing and showed an interest in both sacred and Romani music. Adam began teaching him the piano at age seven, and Franz began composing in an elementary manner when he was eight. He appeared in concerts at Sopron and Pressburg (Hungarian: Pozsony; present-day Bratislava, Slovakia) in October and November 1820 at age 9. After the concerts, a group of wealthy sponsors offered to finance Franz's musical education abroad.

In Vienna, Liszt received piano lessons from Carl Czerny, who in his own youth had been a student of Beethoven and Hummel. He also received lessons in composition from Antonio Salieri, who was then music director of the Viennese court. His public debut in Vienna on December 1, 1822, at a concert at the "Landständischer Saal," was a great success. He was greeted in Austrian and Hungarian aristocratic circles and also met Beethoven and Schubert.[n 3] In spring 1823, when the one-year leave of absence came to an end, Adam Liszt asked Prince Esterházy in vain for two more years. Adam Liszt therefore took his leave of the Prince's services. At the end of April 1823, the family returned to Hungary for the last time. At the end of May 1823, the family went to Vienna again.

Towards the end of 1823 or early 1824, Liszt's first composition to be published, his Variation on a Waltz by Diabelli (now S. 147), appeared as Variation 24 in Part II of Vaterländischer Künstlerverein. This anthology, commissioned by Anton Diabelli, includes 50 variations on his waltz by 50 different composers (Part II), Part I being taken up by Beethoven's 33 variations on the same theme, which are now separately better known simply as his Diabelli Variations, Op. 120. Liszt's inclusion in the Diabelli project—he was described in it as "an 11 year old boy, born in Hungary"—was almost certainly at the instigation of Czerny, his teacher and also a participant. Liszt was the only child composer in the anthology.

After his father's death in 1827, Liszt moved to Paris; for the next five years he was to live with his mother in a small apartment. He gave up touring. To earn money, Liszt gave lessons in piano playing and composition, often from early morning until late at night. His students were scattered across the city and he often had to cover long distances. Because of this, he kept uncertain hours and also took up smoking and drinking—all habits he would continue throughout his life.[4][5]

The following year he fell in love with one of his pupils, Caroline de Saint-Cricq, the daughter of Charles X's minister of commerce, Pierre de Saint-Cricq. However, her father insisted that the affair be broken off.[6] Liszt fell very ill, to the extent that an obituary notice was printed in a Paris newspaper, and he underwent a long period of religious doubts and pessimism. He again stated a wish to join the Church but was dissuaded this time by his mother. He had many discussions with the Abbé de Lamennais, who acted as his spiritual father, and also with Chrétien Urhan, a German-born violinist who introduced him to the Saint-Simonists.[4] Urhan also wrote music that was anti-classical and highly subjective, with titles such as Elle et moi, La Salvation angélique and Les Regrets, and may have whetted the young Liszt's taste for musical romanticism. Equally important for Liszt was Urhan's earnest championship of Schubert, which may have stimulated his own lifelong devotion to that composer's music.[7]

During this period, Liszt read widely to overcome his lack of a general education, and he soon came into contact with many of the leading authors and artists of his day, including Victor Hugo, Alphonse de Lamartine and Heinrich Heine. He composed practically nothing in these years. Nevertheless, the July Revolution of 1830 inspired him to sketch a Revolutionary Symphony based on the events of the "three glorious days," and he took a greater interest in events surrounding him. He met Hector Berlioz on December 4, 1830, the day before the premiere of the Symphonie fantastique. Berlioz's music made a strong impression on Liszt, especially later when he was writing for orchestra. He also inherited from Berlioz the diabolic quality of many of his works.[4]

After attending an April 20, 1832, charity concert, for the victims of a Parisian cholera epidemic, by Niccolò Paganini,[8] Liszt became determined to become as great a virtuoso on the piano as Paganini was on the violin. Paris in the 1830s had become the nexus for pianistic activities, with dozens of pianists dedicated to perfection at the keyboard. Some, such as Sigismond Thalberg and Alexander Dreyschock, focused on specific aspects of technique (e.g. the "three-hand effect" and octaves, respectively). While it has since been referred to the "flying trapeze" school of piano playing, this generation also solved some of the most intractable problems of piano technique, raising the general level of performance to previously unimagined heights. Liszt's strength and ability to stand out in this company was in mastering all the aspects of piano technique cultivated singly and assiduously by his rivals.[9]

In 1833 he made transcriptions of several works by Berlioz, including the Symphonie fantastique. His chief motive in doing so, especially with the Symphonie, was to help the poverty-stricken Berlioz, whose symphony remained unknown and unpublished. Liszt bore the expense of publishing the transcription himself and played it many times to help popularise the original score.[10] He was also forming a friendship with a third composer who influenced him, Frédéric Chopin; under his influence Liszt's poetic and romantic side began to develop.[4]

In 1833, Liszt began his relationship with the Countess Marie d'Agoult. In addition to this, at the end of April 1834 he made the acquaintance of Felicité de Lamennais. Under the influence of both, Liszt's creative output exploded.

In 1835 the countess left her husband and family to join Liszt in Geneva; their daughter[clarification needed] Blandine was born there on December 18. Liszt taught at the newly founded Geneva Conservatory, wrote a manual of piano technique (later lost)[11] and contributed essays for the Paris Revue et gazette musicale. In these essays, he argued for the raising of the artist from the status of a servant to a respected member of the community.[4]

For the next four years, Liszt and the countess lived together, mainly in Switzerland and Italy, where their daughter, Cosima, was born in Como, with occasional visits to Paris. On May 9, 1839, Liszt's and the countess's only son, Daniel, was born, but that autumn relations between them became strained. Liszt heard that plans for a Beethoven monument in Bonn were in danger of collapse for lack of funds, and pledged his support. Doing so meant returning to the life of a touring virtuoso. The countess returned to Paris with the children, while Liszt gave six concerts in Vienna, then toured Hungary.[4]

For the next eight years Liszt continued to tour Europe, spending holidays with the countess and their children on the island of Nonnenwerth on the Rhine in summers 1841 and 1843. In spring 1844 the couple finally separated. This was Liszt's most brilliant period as a concert pianist. Honours were showered on him and he met with adulation wherever he went.[4] Since he often appeared three or four times a week in concert, it could be safe to assume that he appeared in public well over a thousand times during this eight-year period. Moreover, his great fame as a pianist, which he would continue to enjoy long after he had officially retired from the concert stage, was based mainly on his accomplishments during this time.[12]

In 1841, Liszt received an honorary doctorate from the University of Königsberg - an honour unprecedented at the time, and an especially important one from the perspective of the German tradition. Liszt never used 'Dr. Liszt' or 'Dr. Franz Liszt' publicly. Ferdinand Hiller, a rival of Liszt at the time, was allegedly highly jealous at the decision made by the university.[13][14]

In 1841, Franz Liszt was admitted to the Freemason's lodge "Unity" "Zur Einigkeit", in Frankfurt am Main. He was promoted to the second degree and elected master as member of the lodge "Zur Einigkeit", in Berlin. From 1845 he was also honorary member of the lodge "Modestia cum Libertate" at Zurich and 1870 of the lodge in Pest (Budapest-Hungary).[15][16] After 1842, "Lisztomania" swept across Europe. The reception that Liszt enjoyed as a result can be described only as hysterical. Women fought over his silk handkerchiefs and velvet gloves, which they ripped to shreds as souvenirs. This atmosphere was fuelled in great part by the artist's mesmeric personality and stage presence. Many witnesses later testified that Liszt's playing raised the mood of audiences to a level of mystical ecstasy.[17]

Adding to his reputation was the fact that Liszt gave away much of his proceeds to charity and humanitarian causes. In fact, Liszt had made so much money by his mid-forties that virtually all his performing fees after 1857 went to charity. While his work for the Beethoven monument and the Hungarian National School of Music are well known, he also gave generously to the building fund of Cologne Cathedral, the establishment of a Gymnasium at Dortmund, and the construction of the Leopold Church in Pest. There were also private donations to hospitals, schools and charitable organizations such as the Leipzig Musicians Pension Fund. When he found out about the Great Fire of Hamburg, which raged for three days during May 1842 and destroyed much of the city, he gave concerts in aid of the thousands of homeless there.[18]

In February 1847, Liszt played in Kiev. There he met the Polish Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, who was to become one of the most significant people in the rest of his life. She persuaded him to concentrate on composition, which meant giving up his career as a travelling virtuoso. After a tour of the Balkans, Turkey and Russia that summer, Liszt gave his final concert for pay at Yelisavetgrad in September. He spent the winter with the princess at her estate in Woronince.[19] By retiring from the concert platform at 35, while still at the height of his powers, Liszt succeeded in keeping the legend of his playing untarnished.[20]

The following year, Liszt took up a long-standing invitation of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia to settle at Weimar, where he had been appointed Kapellmeister Extraordinaire in 1842, remaining there until 1861. During this period he acted as conductor at court concerts and on special occasions at the theatre. He gave lessons to a number of pianists, including the great virtuoso Hans von Bülow, who married Liszt's daughter Cosima in 1857 (years later, she would marry Richard Wagner). He also wrote articles championing Berlioz and Wagner. Finally, Liszt had ample time to compose and during the next 12 years revised or produced those orchestral and choral pieces upon which his reputation as a composer mainly rested. During this time he also helped raise the profile of the exiled Wagner by conducting the overtures of his operas in concert, Liszt and Wagner would have a profound friendship that lasted until Wagner's death in Venice in 1883. Wagner held strong value towards Liszt and his musicality, once rhetorically stating "Do you know a musician who is more musical than Liszt?",[21] and in 1856 stating "I feel thoroughly contemptible as a musician, whereas you, as I have now convinced myself, are the greatest musician of all times." [22]

Princess Carolyne lived with Liszt during his years in Weimar. She eventually wished to marry Liszt, but since she had been previously married and her husband, Russian military officer Prince Nikolaus zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Ludwigsburg (1812–1864), was still alive, she had to convince the Roman Catholic authorities that her marriage to him had been invalid. After huge efforts and a monstrously intricate process, she was temporarily successful (September 1860). It was planned that the couple would marry in Rome, on October 22, 1861, Liszt's 50th birthday. Although Liszt arrived in Rome on October 21, the Princess declined to marry him that evening. It appears that both her husband and the Tsar of Russia had managed to quash permission for the marriage at the Vatican. The Russian government also impounded her several estates in the Polish Ukraine, which made her later marriage to anybody unfeasible.[23]

The 1860s were a period of great sadness in Liszt's private life. On December 13, 1859, he lost his 20-year-old son Daniel, and on September 11, 1862, his 26-year-old daughter Blandine also died. In letters to friends, Liszt afterwards announced that he would retreat to a solitary living. He found it at the monastery Madonna del Rosario, just outside Rome, where on June 20, 1863, he took up quarters in a small, Spartan apartment. He had on June 23, 1857, already joined the Third Order of St. Francis.[n 4]

On April 25, 1865, he received the tonsure at the hands of Cardinal Hohenlohe. On July 31, 1865, he received the four minor orders of porter, lector, exorcist, and acolyte. After this ordination he was often called Abbé Liszt. On August 14, 1879, he was made an honorary canon of Albano.[23]

On some occasions, Liszt took part in Rome's musical life. On March 26, 1863, at a concert at the Palazzo Altieri, he directed a programme of sacred music. The "Seligkeiten" of his "Christus-Oratorio" and his "Cantico del Sol di Francesco d'Assisi", as well as Haydn's "Die Schöpfung" and works by J. S. Bach, Beethoven, Jommelli, Mendelssohn and Palestrina were performed. On January 4, 1866, Liszt directed the "Stabat mater" of his "Christus-Oratorio", and on February 26, 1866, his "Dante Symphony". There were several further occasions of similar kind, but in comparison with the duration of Liszt's stay in Rome, they were exceptions.

In 1866, Liszt composed the Hungarian coronation ceremony for Franz Joseph and Elisabeth of Bavaria. (Latin: Missa coronationalis) The Mass was first performed on June 8, 1867, at the coronation ceremony in the Matthias Church by Buda Castle in a six-section form. After the first performance the Offertory was added, and two years later the Gradual.[24]

Liszt was invited back to Weimar in 1869 to give master classes in piano playing. Two years later he was asked to do the same in Budapest at the Hungarian Music Academy. From then until the end of his life he made regular journeys between Rome, Weimar and Budapest, continuing what he called his "vie trifurquée" or threefold existence. It is estimated that Liszt travelled at least 4,000 miles a year during this period in his life—an exceptional figure given his advancing age and the rigors of road and rail in the 1870s.[25]

Since the early 1860s there were attempts of some of Liszt's Hungarian contemporaries to have him settled with a position in Hungary. In 1871 the Hungarian Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy made a new attempt. In a writing of June 4, 1871, to the Hungarian King (the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I ). requesting an annual grant of 4,000 Gulden and the rank of a "Königlicher Rat" ("Crown Councillor") for Liszt, who in return would permanently settle in Budapest, directing the orchestra of the National Theatre as well as music schools and further musical institutions.[n 5] By that time there were also plans of the foundation of a Royal Academy for Music at Budapest, of which the Hungarian state should be in charge.

The plan of the foundation of the Royal Academy was agreed by the Hungarian Parliament in 1872. In March 1875 Liszt was nominated as President. The Academy was officially opened on November 14, 1875 under Liszt's colleagues Ferenc Erkel, the director, Kornél Ábrányi and Robert Volkmann and Liszt himself came in March 1876 to give some lessons and a charity concert.

In spite of the conditions under which Liszt had been appointed as "Königlicher Rat", he neither directed the orchestra of the National Theatre, nor did he permanently settle in Hungary.[n 6] Typically, he arrived in mid-winter in Budapest. After one or two concerts of his students by the beginning of spring he left. He never took part in the final examinations, which were in summer of every year. Most of his students were still matriculated as students of either Erkel or later Henri Gobbi. Some of them joined the lessons which he gave in summer in Weimar. In winter, when he was in Budapest, some students of his Weimar circle joined him there.

In 1873, at the occasion of Liszt's 50th anniversary as performing artist, the city Budapest had installed a "Franz Liszt Stiftung" ("Franz Liszt Foundation"). The foundation was destined to provide stipends of 200 Gulden for three students of the Academy who had shown excellent abilities and especially had achieved progress with regard to Hungarian music. Every year it was Liszt alone who could decide which one of the students should receive the money. He gave the total sum of 600 Gulden either to a single student or to a group of three or more of them, not asking whether they were actually matriculated at the Academy.

It was also Liszt's habit to declare all students who took part in his lessons as his private students. As consequence, almost none of them paid any charge at the Academy. Since the Academy needed the money, there was a ministerial order of February 13, 1884, according to which all those who took part in Liszt's lessons had to pay an annual charge of 30 Gulden. However, Liszt did not respect this, and in the end the Minister resigned. In fact, the Academy was still the winner, since Liszt gave much money from his taking part in charity concerts.

The lessons in specific matters of Hungarian music turned out to be a problematic enterprise, since there were different opinions regarding what exactly Hungarian music actually was. In 1881 a new edition of Liszt's book about the Romanis and their music in Hungary appeared. According to this, Hungarian music was identical with the music played by the Hungarian Romanis. Liszt had also claimed in this work that Semitic people, among them the Romanis, had no genuine creativity. Accordingly, within his book, he proposed that they only ever adopted melodies from the country in which they lived. After the book was published, Liszt was accused in Budapest of the spreading of anti-Semitic ideas.[n 7] The following year, there were no students seeking lessons for matriculation in Hungarian music. According to the July 1, 1886 issue of the journal Zenelap, this subject had long since been dropped at the Hungarian Academy.

In 1886 there was still no class for sacral music, but there were classes for solo and chorus singing, piano, violin, cello, organ and composition. The number of students had grown to 91 and the number of professors to 14. Since the winter of 1879–80, the Academy had its own building. On the first floor there was an apartment where since the winter of 1880–81 Liszt lived during his stays in Budapest. His last stay was from January 30 to March 12, 1886. After Liszt's death János Végh, since 1881 vice-president, became president. No earlier than 40 years later the Academy was renamed to "Franz Liszt Akademie". Until then, due to World War I, Liszt's Europe and also his Hungary had died. Mainly, the only connection between Franz Liszt and the "Franz Liszt Akademie" was the name.

On June 24, 1872, the composer and conductor Karl Müller-Hartung founded an "Orchesterschule" ("Orchestra School") at Weimar. Although Liszt and Müller-Hartung were on friendly terms, Liszt took no active part in that foundation. The "Orchesterschule" later developed to a conservatory which still exists and is now called "Hochschule für Musik "Franz Liszt", Weimar".

Liszt fell down the stairs of a hotel in Weimar on July 2, 1881. Though friends and colleagues had noticed swelling in his feet and legs when he had arrived in Weimar the previous month (an indication of possible congestive heart failure), he had been in good health up to that point and was still fit and active. He was left immobilized for eight weeks after the accident and never fully recovered from it. A number of ailments manifested themselves —dropsy, asthma, insomnia, a cataract of the left eye and heart disease. The last-mentioned eventually contributed to Liszt's death. He became increasingly plagued by feelings of desolation, despair and preoccupation with death —feelings which he expressed in his works from this period. As he told Lina Ramann, "I carry a deep sadness of the heart which must now and then break out in sound."[26]

On January 13, 1886, whilst Claude Debussy was staying at the Villa Medici in Rome, Liszt met him there with Paul Vidal and Victor Herbert. Liszt played Au bord d’une source from his Années de pèlerinage, as well as his arrangement of Schubert's Ave Maria for the musicians. Debussy in later years described Liszt's pedalling as "like a form of breathing." Debussy and Vidal performed their piano duet arrangement of Liszt's Faust Symphony; allegedly, Liszt fell asleep during this.[27]

The composer Camille Saint-Saëns, an old friend, whom Liszt had once called "the greatest organist in the world", dedicated his Symphony No. 3 "Organ Symphony" to Liszt; it had premiered in London only a few weeks before the death of its dedicatee.

Liszt died in Bayreuth, Germany, on July 31, 1886, at the age of 74, officially as a result of pneumonia, which he may have contracted during the Bayreuth Festival hosted by his daughter Cosima. Questions have been posed as to whether medical malpractice played a part in his death.[28] He was buried on August 3, 1886, in the municipal cemetery of Bayreuth in accordance with his wishes.[29]

Liszt was viewed by his contemporaries as the greatest virtuoso of his time (although Liszt stated that Charles-Valentin Alkan "had the finest technique of any pianist" known to him).[30] In the 1840s he was considered by some to be perhaps the greatest pianist of all time.[n 8]

There are few, if any, good sources that give an impression of how Liszt really sounded from the 1820s. Carl Czerny claimed Liszt was a natural who played according to feeling, and reviews of his concerts especially praise the brilliance, strength and precision in his playing. At least one also mentions his ability to keep absolute tempo,[31] which may be due to his father's insistence that he practice with a metronome.[32] His repertoire at this time consisted primarily of pieces in the style of the brilliant Viennese school, such as concertos by Hummel and works by his former teacher Czerny, and his concerts often included a chance for the boy to display his prowess in improvisation.

Following the death of Liszt's father in 1827 and his hiatus from the life as a touring virtuoso, it is likely Liszt's playing gradually developed a more personal style. One of the most detailed descriptions of his playing from this time comes from the winter of 1831/1832, during which he was earning a living primarily as a teacher in Paris. Among his pupils was Valerie Boissier, whose mother Caroline kept a careful diary of the lessons. From her we learn that:

M. Liszt's playing contains abandonment, a liberated feeling, but even when it becomes impetuous and energetic in his fortissimo, it is still without harshness and dryness. [...] [He] draws from the piano tones that are purer, mellower and stronger than anyone has been able to do; his touch has an indescribable charm. [...] He is the enemy of affected, stilted, contorted expressions. Most of all, he wants truth in musical sentiment, and so he makes a psychological study of his emotions to convey them as they are. Thus, a strong expression is often followed by a sense of fatigue and dejection, a kind of coldness, because this is the way nature works.

Possibly influenced by Paganini's showmanship, once Liszt began focusing on his career as a pianist again, his emotionally vivid presentations of the music were rarely limited to mere sound. His facial expression and gestures at the piano would reflect what he played, for which he was sometimes mocked in the press.[n 9] Also noted were the extravagant liberties he could take with the text of a score at this time. Berlioz tells us how Liszt would add cadenzas, tremolos and trills when playing the first movement of Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata, and created a dramatic scene by changing the tempo between Largo and Presto.[n 10] In his Baccalaureus letter to George Sand from the beginning of 1837, Liszt admitted that he had done so for the purpose of gaining applause, and promised to follow both the letter and the spirit of a score from then on. It has been debated to what extent he realized his promise, however. By July 1840 the British newspaper The Times could still report

His performance commenced with Händel's Fugue in E minor, which was played by Liszt with an avoidance of everything approaching to meretricious ornament, and indeed scarcely any additions, except a multitude of ingeniously contrived and appropriate harmonies, casting a glow of colour over the beauties of the composition, and infusing into it a spirit which from no other hand it ever received.

During his years as a travelling virtuoso, Liszt performed an enormous amount of music throughout Europe,[36] but his core repertoire always centered around his own compositions, paraphrases and transcriptions. Of Liszt's German concerts between 1840 and 1845, the five most frequently played pieces were the Grand galop chromatique, Schubert's Erlkönig (in Liszt's transcription), Réminiscences de Don Juan, Réminiscences de Robert le Diable, and Réminiscences de Lucia di Lammermoor.[37] Among the works by other composers we find compositions like Weber's Invitation to the Dance, Chopin mazurkas, études by composers like Ignaz Moscheles, Chopin and Ferdinand Hiller, but also major works by Beethoven, Schumann, Weber and Hummel, and from time to time even selections from Bach, Handel and Scarlatti.

Most of the concerts at this time were shared with other artists, and as a result Liszt also often accompanied singers, participated in chamber music, or performed works with an orchestra in addition to his own solo part. Frequently played works include Weber's Konzertstück, Beethoven's Emperor Concerto and Choral Fantasy, and Liszt's reworking of the Hexameron for piano and orchestra. His chamber music repertoire included Hummel's Septet, Beethoven's Archduke Trio and Kreutzer Sonata, and a large selection of songs by composers like Rossini, Donizetti, Beethoven and especially Schubert. At some concerts, Liszt could not find musicians to share the program with, and consequently was among the first to give solo piano recitals in the modern sense of the word. The term was coined by the publisher Frederick Beale, who suggested it for Liszt's concert at the Hanover Square Rooms in London on June 9, 1840,[38] even though Liszt had given concerts all by himself already by March 1839.[39]